On Sunday afternoon at 16:44 EDT.

Sun 2013-09-22 20:44:00 +0000 Sun 2013-09-22 16:44:00 -0400

(Times are to the nearest minute).

On Sunday afternoon at 16:44 EDT.

Sun 2013-09-22 20:44:00 +0000 Sun 2013-09-22 16:44:00 -0400

(Times are to the nearest minute).

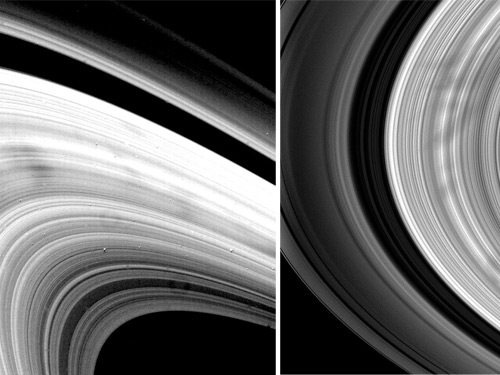

From the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Whether and when NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft, humankind’s most distant object, broke through to interstellar space, the space between stars, has been a thorny issue. For the last year, claims have surfaced every few months that Voyager 1 has “left our solar system.” Why has the Voyager team held off from saying the craft reached interstellar space until now?

[This is a re-post of a blog post I first wrote and posted in 2010-11-12 in Monolith149 Daily. I’ve made some slight edits to the text.]

I was the director of the planetarium at the time and had received a letter from NASA that they were broadcasting live coverage of the Voyager 1 encounter via satellite.

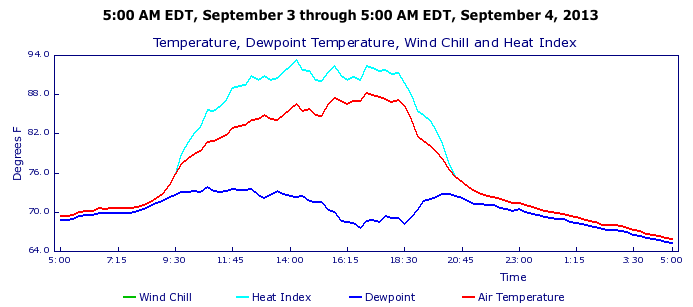

A friend recently told me about georgiaweather.net.

Via @PTTU

New American Rocket Making Launch Debut with Friday Moon Shot By Mike Wall, Senior Writer at Space.com

A Minotaur V rocket will carry NASA’s Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer spacecraft (LADEE) on its maiden launch, which is slated to take place Friday at 11:27 p.m. EDT (0327 GMT) from the space agency’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia.

The first three stages of the Minotaur V (and the Minotaur IV) are solid rocket motors recycled from decommissioned Peacekeeper intercontinental ballistic missiles. The fourth and fifth stages are commercial Star motors, which are also flight-proven, [Wallops launch manager Doug] Voss said.

The $280 million LADEE mission aims to study lunar dust and the moon’s wispy atmosphere from orbit using three science instruments.

[Space.com] Editor’s note: Weather permitting, Friday’s launch could be visible across wide regions of the U.S. East Coast.

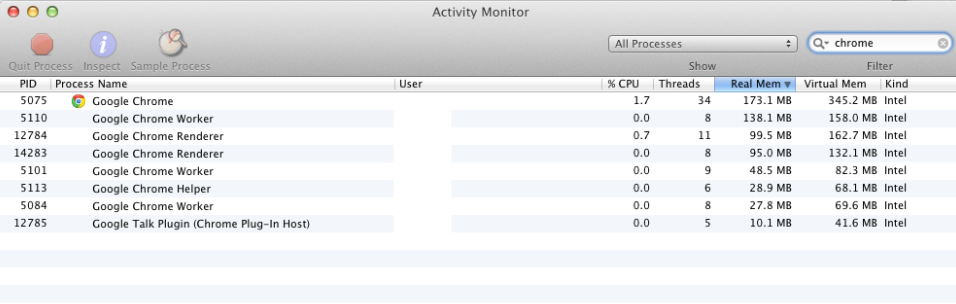

Here’s a comparison of Opera and Chrome memory with just three or four tabs open. (This is not a careful test).

In this case, Chrome is using 621 MB (612 KF2) of real memory vs. Opera’s 458 MB (458 KF2).

I heard Clayton Morris on this weekend’s TWIT about the poll question “What are your top five phone apps?”

I was wondering about my answer. Well, let me take out my phone and have a look.

I’ll assume the calling app (the little phone handset) doesn’t count. I’m not sure about the Clock app counts either. If it did, it would be near the top, too.

Trying to sort some of the apps on my home screens by most used, I come up with.

If I remove what came on the pure Google Android OS (Currently 4.2.2), and focus on the apps I downloaded from the app store, then that leaves the following.

Runners up which might actually belong on this list, but I’m not really sure which I truly use the most over others. I use them all quite a bit.

Via @HNTweets

Smalltalk runtime in the browser: http://amber-lang.net/ Comments: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=6216539

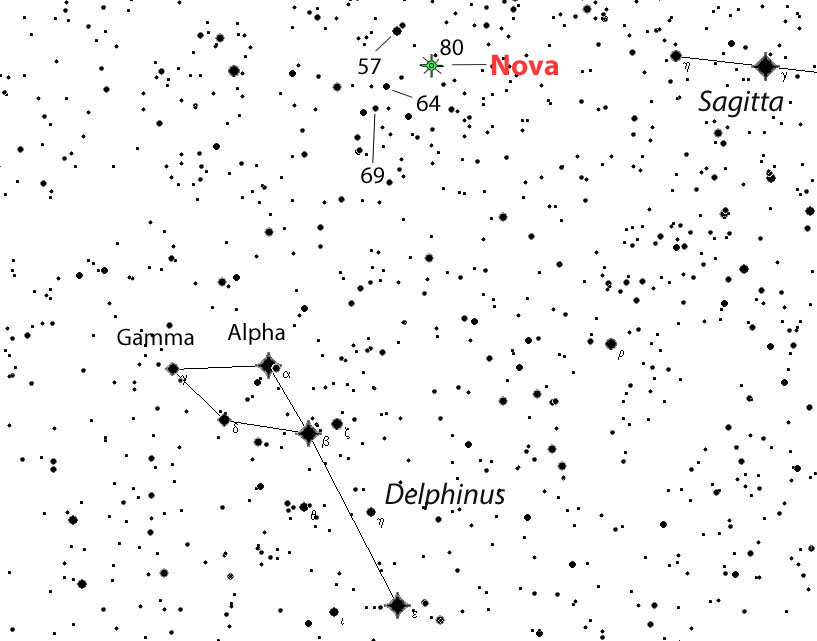

There’s a nova in Delphinus.

From Astro Bob

Earlier today Japanese amateur astronomer Koichi Itagaki photographed a new bright nova in the constellation Delphinus (del-FYE-nuss). At the time it was a little below the naked eye limit (6.8 magnitude) but it’s since risen to around 6. That means observers with dark skies can see our new guest without optical aid. And if you don’t have dark skies, don’t worry. You’ll spot the star in any pair of binoculars.

2013 08 14.952 Photometry: B=6.72, V=6.66, R=6.32, B-V=+0.06 (a Hipparcos reference star), remotely using 0.43-m f/6.8 astrograph + CCD (RAS observatory, Nerpio, Spain, I89). Observer T. Yusa, Osaki, Japan.

In the Update from Universe Today:

Since showing itself on August 14, 2013, a bright nova in the constellation Delphinus — now officially named Nova Delphini 2013 — has brightened even more. As of this writing, the nova is at magnitude 4.4 to 4.5, meaning that for the first time in years, there is a nova visible to the naked eye — if you have a dark enough sky. Even better, use binoculars or a telescope to see this “new star” in the sky.

A less-awkward usage occurred to me yesterday for the KF notation. Instead of referring to four gigbytes (4 GB) as “4 3-KF” use “4 KF3”. So the scheme becomes KB = KF1, MG = KF2, GB = KF3, TB = KF4, PB = KF5, and so on.

Early microcomputers had a maximum memory of 64 KF1. The early IBM PC architecture had 640 KF1 of useable memory when there was 1 KF2 of RAM.

It hasn’t been that long ago that 512 KF2 or even 640 KF2 were common in modern PCs. Today several KF3 are common and 10 or 20 KF3 in big servers.

Now it’s not uncommon for a home user to have one or several KF4 of disk space.

Corporate data stores can easily span several KF5 and get into the KF6. Reports of data resources in the KF7 realm are starting to surface..

Original post: KF Notation for Big Numbers